Diabetic Eye Disease Fact Sheet

What is Diabetes?

Diabetes is a disease that affects the body’s ability to produce or use insulin effectively to control blood sugar (glucose) levels. Too much glucose in the blood for a long time can cause damage in many parts of the body. Diabetes can damage the heart, kidneys, and blood vessels. It damages small blood vessels in the eye as well. Even if diabetes is well controlled, it can affect your regular eye care.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that having a yearly eye exam, or mas recommended by an ophthalmologist, can prevent about 90% of diabetes-related vision loss. People with diabetes should get these critical, annual eye exams, even before they have signs of vision loss. Studies show that sixty percent of diabetics are not getting the exams their doctors recommend.

What is Diabetic Eye Disease?

Diabetic eye disease is a term for several eye problems that can all result from diabetes. Diabetic eye disease includes: diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema, cataract, and glaucoma.

Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy is when blood vessels in the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye, swell, leak or close off completely. Abnormal new blood vessels can also grow on the surface of the retina. People who have diabetes or poor blood sugar control are at risk for diabetic retinopathy. Risk also increases the longer someone has diabetes.

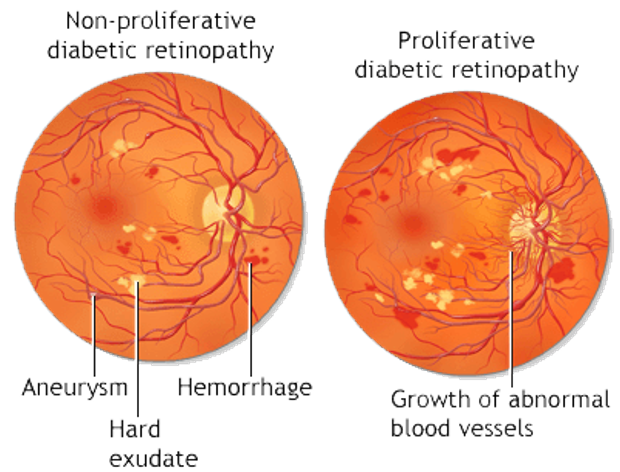

There are two main stages of diabetic retinopathy, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). NPDR is the early stage of diabetic retinopathy. Many people with diabetes have it. With NPDR, tiny blood vessels leak, making the retina swell. NPDR can also cause blood vessels in the retina to close off. This is called macular ischemia. When that happens, blood cannot reach the centermost portion of the retina, called the macula. Sometimes tiny particles called exudates can form in the retina. These can affect your vision too.

PDR (proliferative diabetic retinopathy) is the more advanced stage of diabetic retinopathy. It happens when the retina starts growing new blood vessels. This is called neovascularization. These fragile new vessels often bleed into the vitreous, a clear gel that fills the space between the lens and the retina. If they only bleed a little, you might see a few dark floaters. If they bleed a lot, it might block all vision. The new blood vessels can also form scar tissue. Scar tissue can cause problems with the macula or lead to a detached retina. PDR is very serious and can steal both your central and peripheral (side) vision.

Images of NPDR and PDR courtesy of Specialty Eye Institute

Diabetic Macular Edema

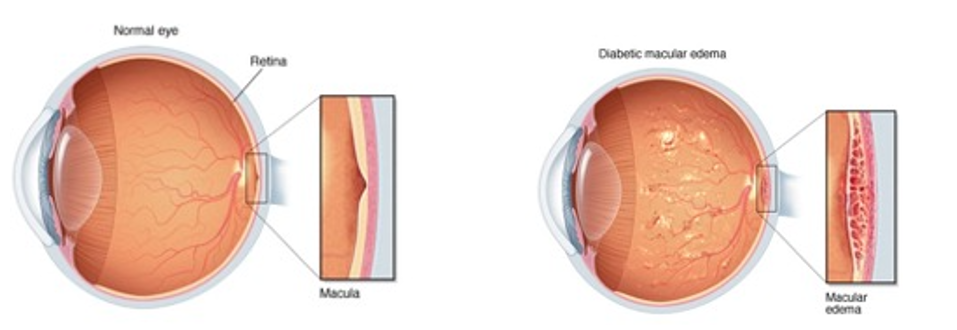

When diabetic retinopathy causes the macula to swell, it is called diabetic macular edema (DME). If you have DME, your vision will become blurry because the extra fluid in your macula keeps it from working properly. This is the most common reason why people with diabetes lose their vision.

Normal eye vs. eye with diabetic macular edema

Images courtesy of the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research

Diabetes and Cataracts

Excess blood sugar from diabetes can cause cataracts. You may need cataract surgery to remove lenses that are clouded by the effects of diabetes. Maintaining good control of your blood sugar helps prevent permanent clouding of the lens and surgery.

Eye with diabetic cataract

Image courtesy of American Academy of Ophthalmology

Diabetes and Glaucoma

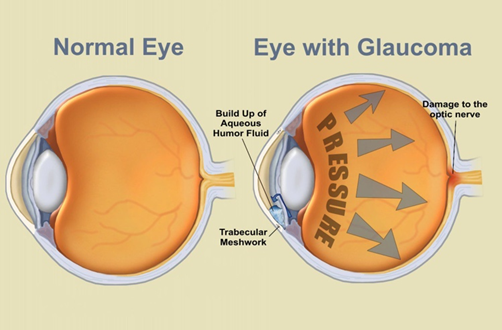

Glaucoma is a group of diseases that cause damage to your eye’s optic nerve, a nerve at the back of your eye that connects and sends light signals to your brain so you can see. This damage leads to irreversible loss of vision. Having diabetes doubles your chance of getting glaucoma.

Normal eye vs. eye with glaucoma

Image courtesy of Prevent Blindness

What Are the Symptoms of Diabetic Eye Disease?

You can have diabetic retinopathy and not know it. This is because it often has no symptoms in the early stages. As diabetic retinopathy gets worse, you will notice symptoms such as: seeing an increasing number of floaters, having blurry vision, having vision that changes sometimes from blurry to clear, seeing blank or dark areas in your field of vision, having poor night vision, noticing colors appear faded or washed out, and losing vision. Diabetic retinopathy symptoms usually affect both eyes.

Diabetic macular edema can cause blurry vision, metamorphopsia (a visual distortion in which straight lines appear curved), changes in color vision, and difficulty reading. However, you can also have no symptoms with DME.

Glaucoma causes blind spots in the visual field. People with glaucoma slowly lose side vision.

Vision with glaucoma

Photo courtesy of the National Eye Institute, NIH

Cataracts cause things to look blurry, hazy or less colorful.

Vision with cataracts

Photo courtesy of the National Eye Institute, NIH

How is Diabetic Eye Disease Diagnosed?

Drops will be put in your eye to dilate (widen) your pupil. This allows your ophthalmologist to look through a special lens to see the inside of your eye.

Your doctor may do optical coherence tomography (OCT) to look closely at the retina. A machine scans the retina and provides detailed images of its thickness. This helps your doctor find and measure swelling of your macula.

Fluorescein angiography or OCT angiography helps your doctor see what is happening with the blood vessels in your retina. Fluorescein angiography uses a yellow die called fluorescein, which is injected into a vein (usually in your arm). The dye travels through your blood vessels. A special camera takes photos of the retina as the dye travels throughout its blood vessels. This shows if any blood vessels are blocked or leaking fluid. It also shows if any abnormal blood vessels are growing. OCT angiography is a newer technique and does not need dye or injections to look at blood vessels.

How is Diabetic Eye Disease Treated?

Your treatment is based on what your ophthalmologist sees in your eyes. Treatment options may include:

Medical control: Controlling your blood sugar and blood pressure can stop vision loss. Carefully follow the diet your nutritionist has recommended. Take the medicine your diabetes doctor prescribed for you – sometimes, good sugar control can even bring some of your vision back! Controlling your blood pressure keeps your eye’s blood vessels healthy.

Medicine: One type of medication is called anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) medication. These include Avastin, Eylea, and Lucentis. Anti-VEGF medication helps to reduce swelling of the macula, slowing vision loss and perhaps improving vision. This drug is given by injections (shots) in the eye. A newer drug called faricimab (Vabysmo) can also be injected into the eye. It targets two proteins involved in the proliferation of abnormal new blood vessels. Steroid medicine is another option to reduce macular swelling. This is also given as injections in the eye. Your doctor will recommend how many medication injections you will need over time.

Laser surgery: Laser surgery might be used to help seal off leaking blood vessels. This can reduce swelling of the retina. Laser surgery can also help shrink blood vessels and prevent them from growing again. Sometimes more than one treatment is needed.

Vitrectomy: If you have advanced PDR, your ophthalmologist may recommend surgery called vitrectomy. Your ophthalmologist removes vitreous gel and blood from leaking vessels in the back of your eye. This allows light rays to focus properly on the retina again. Scar tissue also might be removed from the retina.

What Other Eye Problems Are Related to Diabetes?

Diabetes can cause vision problems even if you do not have a form of diabetic eye disease. If your blood sugar levels change quickly, it can affect the shape of your eye’s lens, causing blurry vision. Your vision goes back to normal after your blood sugar stabilizes. Have your blood sugar controlled before getting your eyeglasses prescription checked, to ensure you receive the correct prescription.

Diabetes can also damage the nerves that move the eyes and help them work together. This nerve damage can lead to double vision.

Diabetes is a risk factor for several other eye diseases. They include branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) and central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), where vein(s) from the retina become blocked.

How Can You Protect Your Vision?

To prevent eye damage from diabetes, maintain good control of your blood sugar. Follow your primary care physician’s diet and exercise plan. If you have high blood pressure or kidney problems, ask your doctor about ways to manage and treat these conditions. If you have not had an eye exam with an ophthalmologist, it is crucial to get one now. Be sure to never skip the follow-up exams that your ophthalmologist recommends and get a comprehensive dilated eye examination from your ophthalmologist at least once a year. If you notice vision changes in one or both eyes, call your ophthalmologist right away. Get treatment for diabetic retinopathy as soon as possible. Early treatment is the best way to prevent vision loss.

What is the Latest Research on Diabetic Eye Disease?

Injections of medications into the eye are a vital treatment for diabetic eye disease, but the burdens that monthly or every-other-month injections impose on patients are well-known to be barriers to care for many people. Making treatment less onerous has driven research into new treatments since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ranibizumab (Lucentis) in 2012 as the first anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) medication for the treatment of diabetic macular edema.

In 2023, the FDA approved a high dose form of the anti-VEGF drug aflibercept (Eylea HD) for DME and diabetic retinopathy. The 8-mg formulation of aflibercept is a more potent version of the 2-mg product (Eylea), but the higher dose is designed to be given every 2-4 months, whereas the original formulation is recommended for monthly or every-other-month use.

A combination therapy that has shown promise in a phase 2 trial is a drug called UBX125 in combination with the anti-VEGF drug aflibercept. In the trial, 40% of patients didn’t need a supplemental injection through 48 weeks, and 64% went treatment-free for more than 24 weeks.

A novel drug delivery system that could stretch out intervals between injections is also in human trials. The refillable port delivery system (PDS) implant with ranibizumab (Susvimo) is in phase 3 trials for DME and was previously approved for age-related macular degeneration. PDS is a small cylinder implanted into the eye and filled with the anti-VEGF drug ranibizumab, to be released for 6 months or so, then refilled in the physician’s office when it’s empty. While new implants of PDS were halted in 2022 after the manufacturer (Genentech) received reports of device leakage, Genentech said it has fixed those problems.

Topical eye drops are commonly used for glaucoma, eye infections and inflammation, but using them for retinal disease has been a challenge. By the time the drug reaches the back of the eye, it has lost much of its pharmacokinetic activity. Three drops are in clinical trials for diabetic eye disease, with one, OCS-01, a preservative-free formulation of the corticosteroid dexamethasone, scheduled this year to enter a phase 3 trial.

Gene therapy is also poised to be helpful for diabetic eye disease. There are currently several clinical trials underway for gene therapies to treat DME. While approved gene therapies for diabetic eye disease are years away, early research has shown some promising results, and patients may only need one or two injections.

In addition to these advances, at least four oral tablets are in early-stage human trials for diabetic eye disease. Thus, the future looks bright for new diabetic eye disease treatments that require fewer or no injections.

For more information on diabetic eye disease, you can subscribe to the free monthly e-mail diabetes and diabetic eye disease research update. Contact thl@vistacenter.org.

Sources:

Turbert, David. “Diabetic eye disease.” American Academy of Ophthalmology, 14 Oct. 2021, www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/diabetic-eye-disease

Boyd, Kierstan. “Diabetic Retinopathy: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment.” American Academy of Ophthalmology, 27 Nov. 2023, www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-diabetic-retinopathy

Jacoba, Cris Martin P., MD, et al. “Diabetic Macular Edema.” American Academy of Ophthalmology EyeWiki, 2 Nov. 2023, www.eyewiki.org/Diabetic_Macular_Edema

Kirkner, Richard Mark. “Will 2024 be easier on the eyes?” Medscape Medical News, 28 Feb. 2024, https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/will-2024-be-easier-eyes-2024a10003yn

Kirkner, Richard Mark. “Retina Outlook: New Drugs, Return of an Implant, as Biosimilars Stall.” Medscape Medical News, 22 Feb. 2024, https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/retina-outlook-new-drugs-return-implant-biosimilars-stall-2024a10003ij

Compiled/edited by M. Kaplan, PhD, 5/2024

Information Disclaimer: We do not recommend any particular treatment. Our Material might not represent all that is available on the subject. This information might not apply specifically to your own condition. Our Material is not intended as a substitute for medical care. Our Material should be used to formulate questions for discussion with your physician. We hope that the information you find at The Health Library will be useful in communicating with your health professionals. If you have any questions about your unique medical condition, we strongly advise that you see your physician.